WHITE OAK, INDIA INK // SPRING 2024 // RHODE ISLAND SWISS MOUNTAIN CHAIR

The Swiss mountain chair, also known as the Tyrolean chair (after the Tyrol region of the Alps) or simply the “folk chair” or “back stool”, is a loose collection of vernacular forms that emerged in and around central Europe in the late Middle Ages. The base is rustic, almost pure utility. The legs are usually tapered octagons (a shape that doesn’t require a lathe), staked through the seat with wedged tenons, or through battons if the seat was too thin. The edge of the seat is often eased in a very simple fashion. In contrast, the backs are often quite ornamented, sometimes simply through their profile and sometimes through elaborate hand carving of highly symbolic imagery. The patterns and profiles cover a surprisingly wide aestetic range, and almost all are unique, even within sets that resided in a single home. This humble wedding of utility and beauty is what attracted me to these chairs as a case study, and as an opportunity to explore a new kind of generative variety.

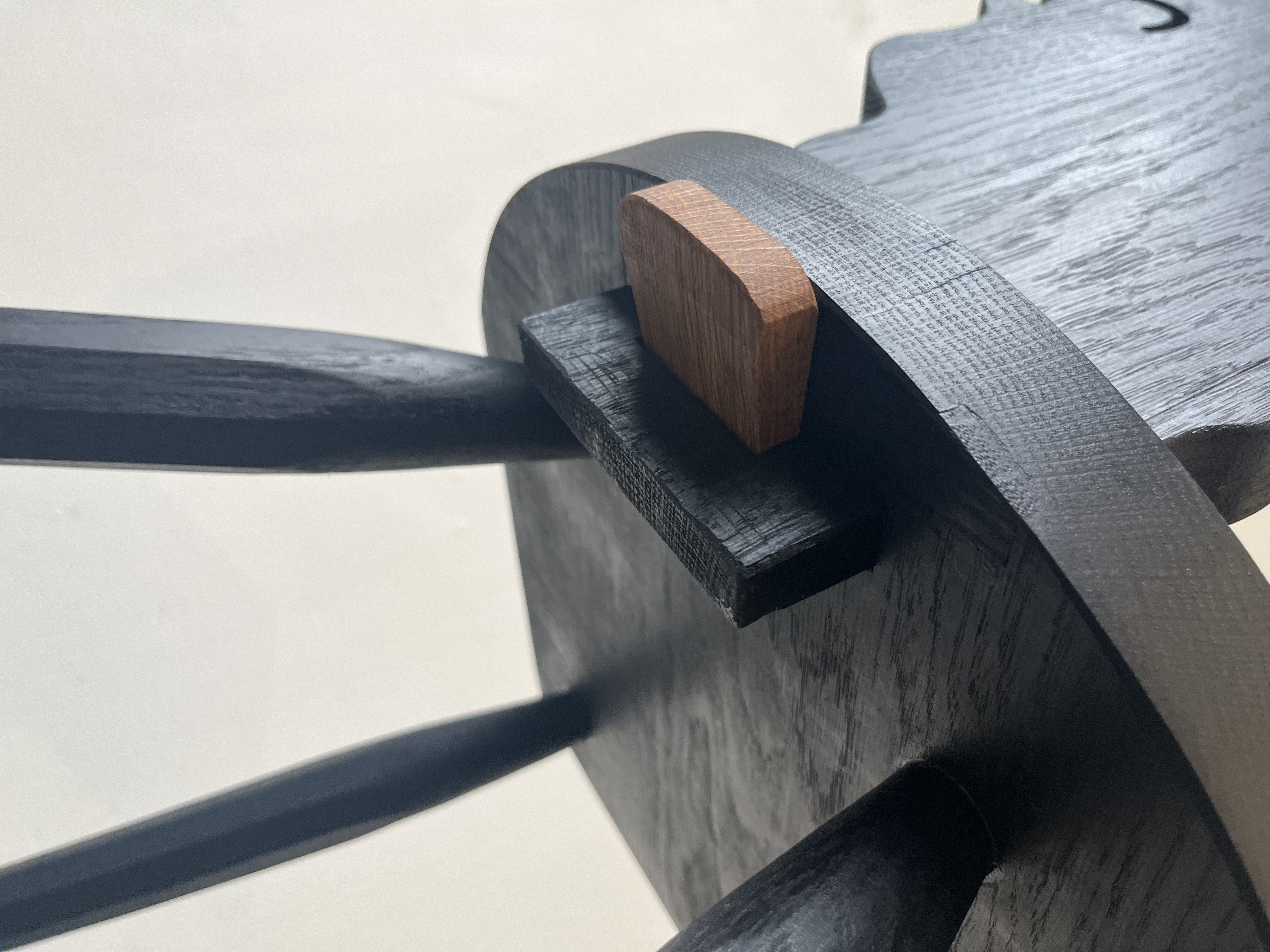

My version leaves the base essentially untouched: staked octagonal legs, hand-shaped, with wedged tenons that poke through the seat. The back, however, is one output among many from an generative algorithm which produces a series of unique patterns which are carved with a CNC milling machine.

These chairs emerged at a time when Switzerland was in the middle of profound social and cultural changes. A strong artisan class was emerging and self-organizing into what would become the first Medieval trade guilds - worker organizations that have been a continuous source of inspiration from the Arts & Crafts movement to the Bauhaus, and which have been looked back on as a model for economically and socially viable craft production. This was a time when craftspeople were a real part of the economic and civic life of the city, and the fruits of their labor were the primary artifacts of culture. Contrast this with today, where craft is relegated to the extremes -- high-end studio or luxury craft on one end, hobby and DIY on the other -- while the fat middle is filled with “products” (the fruits of the industrial designer’s labor).

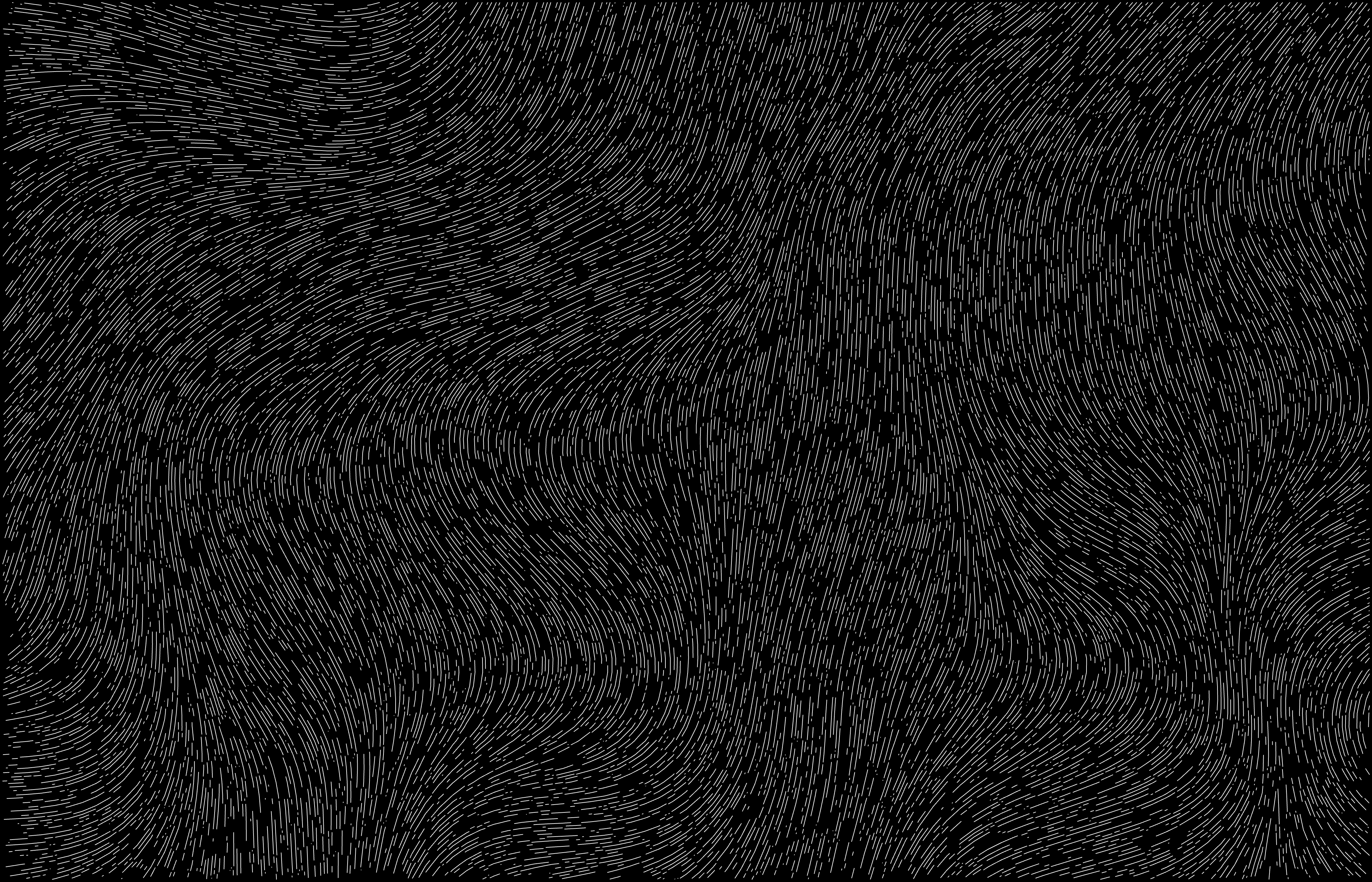

For the design of the back I wanted something that would mimic the expressive and playful shapes that are found in historical examples of these types of chairs. After a few iterations, I landed on what are called flow fields -- a technique that’s a major cliche in generative art circles, but ended up being perfect for generating smooth, playful curves with a wide aesthetic range.

Once the pattern is generated, the lines are exported as vector graphics, and then turned into a toolpath for a CNC milling machine. The algorithm has parameters which tailor the pattern to a given standard tool diameter and profile. The pattern shown on the prototype used a 1/4” ball end mill, for example.

The base of the chair is made in nearly the same way it would have been 600 years ago. The legs are tapered octagons - a shape that doesn’t require a lathe - which are “staked” through the seat with conical tenons. The edge of the seat is chamfered on the top edge for comfort rather than the bottom for aesthetics.

The prototype produced for this project was stained with black india ink, one of the oldest inks used for writing -- a nod to the fact that the design process was something rather akin to creative writing. The majority of my input as a designer was in the form of language: from the javascript that generates the patterns, to the SVG output code, and finally to the G-code that instructs the CNC machine.